In 1862, during his journey through Spain, the Danish poet Hans Christian Andersen seizes the chance to visit the city of Tangier in Morocco, a mere 40 kilometers as the crow flies from the southernmost point of Spain.

A visit to Africa, as he calls it.

Hans Christian Andersen is staying with the British ambassador and his Danish wife, in a beautiful coastal mansion. One late afternoon, he sits on the terrace, with a swarm of fishing boats dotting the Strait of Gibraltar in the background, and enjoys a Cuban cigar, a true Havana. The smoke dissolves into the still, warm air. From that smoke, a miniature fairy tale begins to take shape:

In Cuba stood black girls, cutting tobacco plants; their eyes glittered like stars, but the eyes of the youngest among them glittered more than the rest. She was a king's daughter from hot Africa, now a slave in a large West India island.

There fell a tear on the leaf she had just cut from the tobacco plant; there is a soul in a tear; a soul can never die, and this contained the memories of her childhood, longing, and regret. The leaf was rolled up, -the brown mummy was called a good cigar.

It was the very one I had just lighted, here, on the coast of Africa; it steamed, the smoke, undulating, extended itself; it became a little cloud-land, a dreamworld. What lay in it ? A soul, a tear from Africa's daughter.

It freed itself, it raised itself in its fatherland, and flew over the Atlas mountains to the unknown inner region. The soul in the tear was at liberty in thought's homeland!

Translation by Mrs Anne Anne Bushby (1864)

A sociopolitical manifesto

This story is a small stroke of genius and a sociopolitical manifesto from the poet. I’ll admit, I didn’t catch the political undertone the first few times I read this little tale. I doubt many of Andersen's patrons in Denmark did either, when they read his travelogue from Spain. That might have been just as well, for many of their family fortunes could, directly or indirectly, be traced back to slave trade or, at the very least, production rooted in slave labor. The director of the powerful foundation Ad Usos Publicos, which sent the young Andersen to Latin school in 1822, was Denmark’s largest slave owner, with no less than four plantations on St. Croix.

The context for the tale

In this, as in many of Andersen's other tales, there is a universal human core. The refined manner in which it is presented becomes even clearer when we consider the context of that time.:

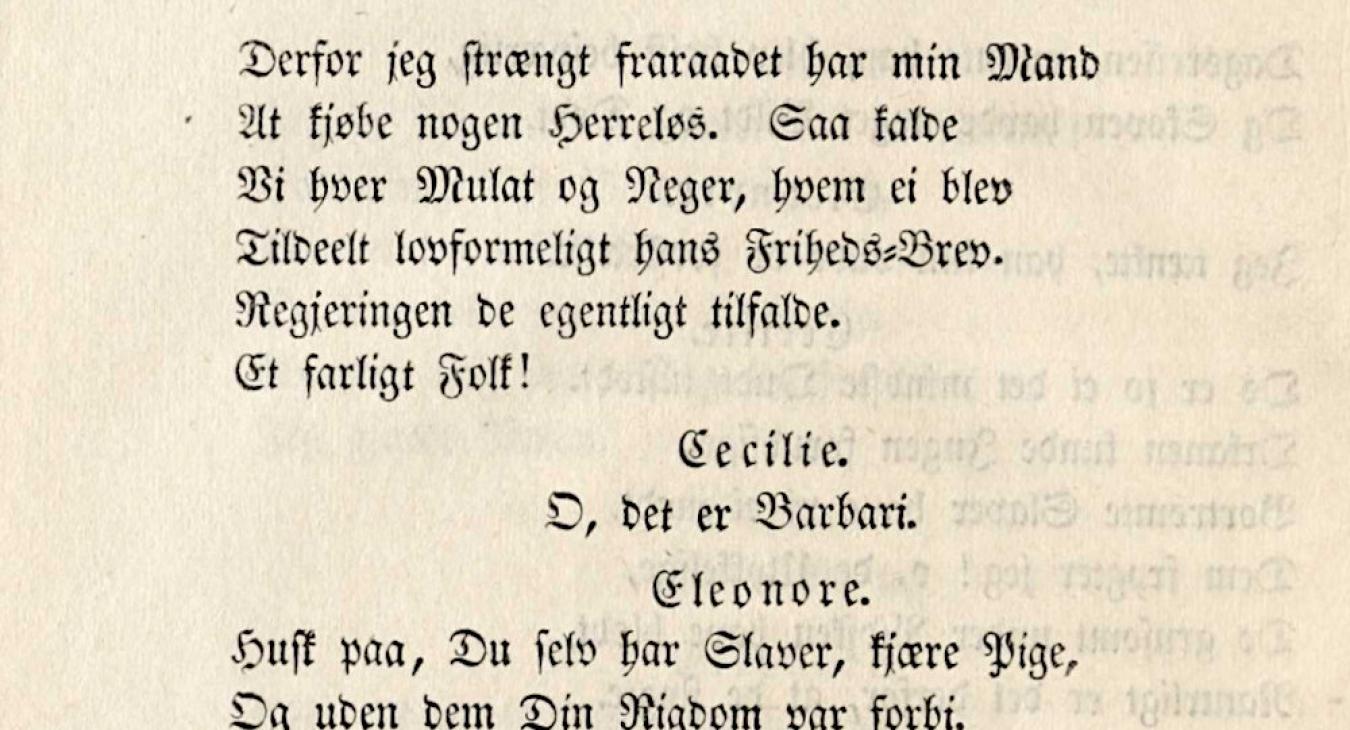

1. - Denmark had abolished the slave trade by law as early as the beginning of the 19th century. In the decades that followed, however, public debate continued on the humanitarian aspects of slave labor and the economic impact of a full prohibition. In 1839, Andersen wrote a critically acclaimed romantic drama, The Mulatto, in which slavery in the Danish colonies in the West Indies was a central theme.

By the time of Andersen’s journey to Spain, slavery had, in practice, been abolished in a long list of European countries, including England (1834) and Denmark (1848), while in the Spanish colonies, slave labor was still in use. The humanist ideals that had begun to take hold during the Enlightenment had finally triumphed in Northern Europe, though not everyone among society’s upper echelons welcomed this more humane restructuring of the economy.

2. - It was precisely the disagreement on the issue of slave labour that had led the United States into a civil war, raging at the very time Andersen sat writing on the terrace in Tangier. Although news traveled slowly in those days, one can easily imagine that Andersen, who was staying with the British ambassador, had some awareness of the situation in America. Slavery was abolished there by law in 1863, though the war continued until 1865. In Cuba, which was still a Spanish colony, slavery persisted until as late as 1886..

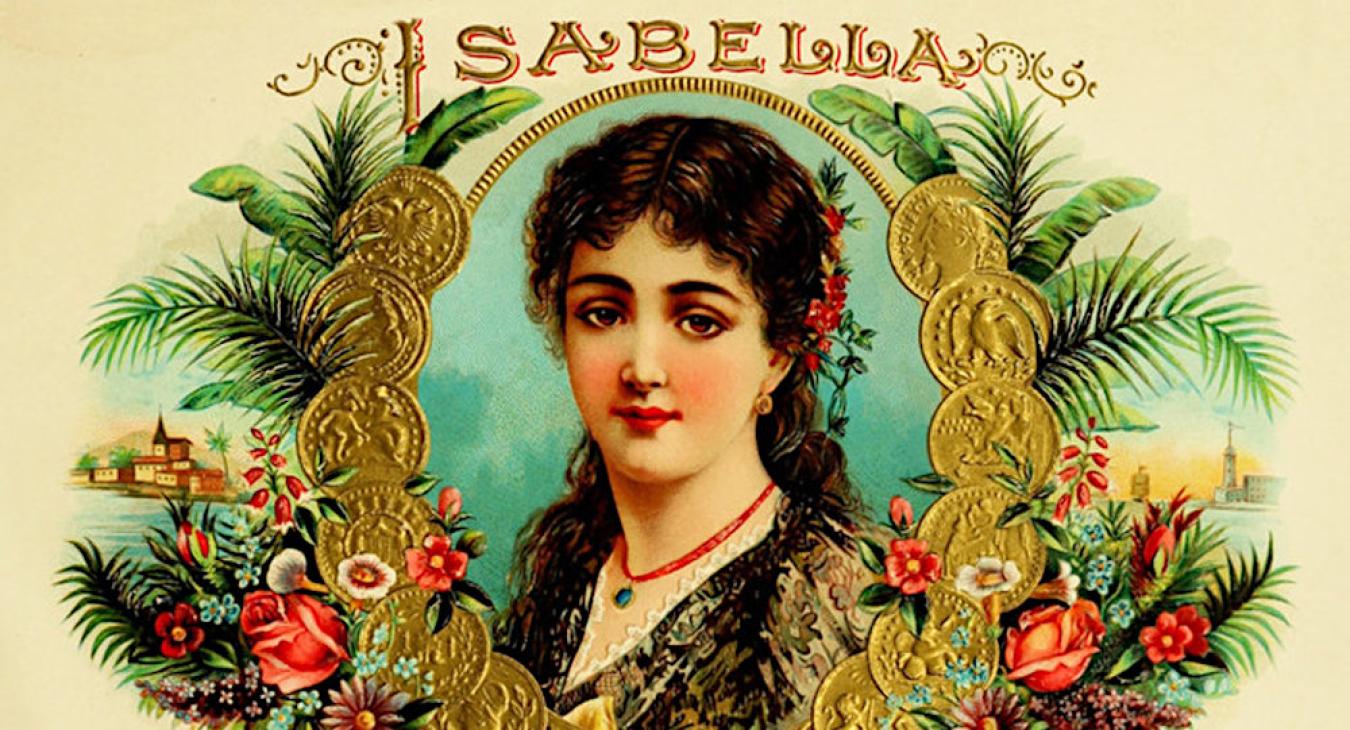

3. - Although the history of tobacco stretches back to the time before Columbus, it wasn’t until the early 1800s that an independent Cuban tobacco industry truly gained ground. For centuries, tobacco leaves had been exported in sacks, but it was now understood that a cigar’s longevity improves if it is rolled immediately after the leaves are harvested. By 1859, Cuba was home to a full 10,000 tobacco plantations and numerous prestigious brands, some of which still exist today.

By the mid-1800s, cigar smoking was thoroughly in vogue, especially among the upper social circles in Europe and the United States. There was a certain prestige associated with smoking genuine Cuban cigars. The many different cigar brands competed to attract customers with elaborate logos and decorative cigar boxes.

Andersens tale in a new light

So, when Andersen lights his Cuban cigar, he follows the fashion of the era. He is a man of his time—in the company of the elite from both Europe and the United States. Also, he lights his cigar fully aware that it was produced in a country where much of the labor force is enslaved.(1)

With this context in mind, please try reading the story once more, or listen to the Danish soprano Anna Wierød as she recites the text to the strains of a Cuban popular melody.

1) In reality, Cuban cigar production was primarily carried out by poor immigrants from the Canary Islands.